Children’s Memories of Past Lives Redefine What It Means to Be Dead

Reincarnation is one of consciousness’s greatest and most complex accomplishments. In The Last Frontier, I wrote a great deal about it—what it can and cannot contribute toward proof of survival after death, for instance, and about the phenomena associated with reincarnation, such as xenoglossy (speaking a language known only from a past life), and why there is no karma or karmic debt. To the best of my ability, I explained how reincarnation works in simultaneous time, a fascinating aspect of consciousness I hope to cover in more depth in my next book. Obviously I cannot do justice to such hefty topics in short website articles. But I can present some of the material in bits and pieces. This post is one of those pieces.

Reincarnation is one of consciousness’s greatest and most complex accomplishments. In The Last Frontier, I wrote a great deal about it—what it can and cannot contribute toward proof of survival after death, for instance, and about the phenomena associated with reincarnation, such as xenoglossy (speaking a language known only from a past life), and why there is no karma or karmic debt. To the best of my ability, I explained how reincarnation works in simultaneous time, a fascinating aspect of consciousness I hope to cover in more depth in my next book. Obviously I cannot do justice to such hefty topics in short website articles. But I can present some of the material in bits and pieces. This post is one of those pieces.

An article by Jim Tucker of the University of Virginia (Edge Science 17, February 2014) gave me a launching point for starting one discussion of just one tiny corner of this creative and wildly flexible function of consciousness—children’s memories of past lives. My explanations for why some children have more extensive memories than others enters into little known territory in afterlife studies—that dead and alive are not about the body. You are only “dead” when your consciousness stops focusing in physical reality.

Tucker, successor to the celebrated reincarnation researcher, Ian Stevenson, draws strong parallels between the “afterlife” and the dream world in order to better conceptualize the afterlife. Sometimes the parallels help, but just as often they are misleading. Thinking in this direction, however, does bring us closer to breaking down our concepts of the afterlife as a single dimension where all the dead go or, worse, a place. More about this later in a future post.

The children who have come to the attention of Tucker and Stevenson had spectacular spontaneous memory of their previous lives. They tend to be quite young at the time of recall, usually under the age of seven. Four-year olds predominate in this group, but when an even younger child has exceptional communication skills, memory proves to be very sharp. Although almost all young children remember past lives, usually acted out in play, few of them are brought to researchers.

Parental attitudes do more than anything else to repress conscious knowledge of personal lives in other bodies. My own experience at the age of three is unfortunately common. When I attempted to tell my mother that I was a male in another life, she scolded me for making up stories. No doubt she was alarmed, especially by what she must have perceived as sexual confusion on my part. Largely from social conditioning, recall is all but absent by the time kids reach their teens. Oddly it reappears briefly between the ages of 18 and 23. After that, most of us have to wait for the help of regression therapists or hypnotists to bring those memories back. A light relaxation is really all it takes, and you don’t need a facilitator. So far, no one working with a professional has failed to recall another life. We all have these memories. We just bury them alive.

If so, then why do some children have such detailed memories and others don’t? One reason is because the exceptional children under study reincarnated soon after dying in their former lives. Tucker found that the averaged interval between death and rebirth is only sixteen months. This is an astonishing finding and contrary to the common belief that at least a century passes before reincarnating. The implications here are enormous. Stevenson found some children with accuracy rates in the upper ninety-percent range. Accuracy rates can be calculated easily because these children reincarnate so quickly. Their families and friends from their previous lives are consequently still alive and able to confirm or refute the children’s recollections.

The children frequently reincarnated in the same area, sometimes even in the same family, making verification all the easier. In over ninety percent of the cases in the University of Virginia files, a person reincarnates in the same country, and often near their former homes. Even when a child remembers being someone from another country, there is still a connection. Tucker gives the example of Burmese children who have talked about having been Japanese soldiers who were killed in Burma during World War II.

In an astounding seventy percent of their cases, the previous person died from unnatural causes, namely murder, suicide and accidents. Obviously, this is a key point. And they tend to have died quite young, with the mean age being only twenty-eight. For those who died of natural causes, their median age was still only thirty-five, and twenty-five percent of those deaths occurred at the age of fifteen or younger. Clearly, early deaths present another key point.

As a medium, I have encountered a many, many people who died of unnatural causes, be it suicide, murder, or accident. Generally, they are in shock directly afterward. In deaths by accident or murder, shock may be mixed with rage that their lives were cut short. Here I think of a dead policeman who I encountered on the street who had just been shot in the chest. He was not just in shock and rage, but also in grief over leaving his two young sons. The poor man was totally unable to get his bearings and looking for a way to come back. Others are confused or in denial of their deaths. All of the above can apply to those who died young of natural causes as well, that is, if they were in denial of their terminal condition before death.

In all these circumstances, the deceased’s first reactions are typically to return to physical life as quickly as possible. Whether or not they ever believed in reincarnation, instinct takes over and they mentally scan friends and family to whom they can reincarnate. If there is no immediately viable opportunity, they will scan the general region in which they lived. This scanning is accomplished in seconds, by the way. In several cases of suicide I’ve worked with, they were horrified by the mistake they made and the violence they had done to themselves. They wanted to come back to this world instantly to undo it. I usually have to work very hard to break through their shock and keep their attention in order to stop them from shooting off to someone who seems ready for pregnancy. But what if I hadn’t stopped them? Given the number of unnatural deaths that go on in our world every second, presumably only an infinitesimal few have someone there who knows how to get their attention and redirect them.

This mindless urgency to return as quickly as possible explains the short period of 16 months between death in one life and rebirth in another. And the scanning partly explains why so many return to the same family or region. Let me give you an example. Within seconds after his death, a university professor who shot himself in New York located a friend of his living in Ohio, who was ready to have a child. Had I not interfered, he would be about 12 years old by now. The Burmese children mentioned above, who were formerly Japanese soldiers in Burma killed in battle also follow this scanning profile. I believe the shock factor, the illogical urgency to come back, is the reason why people who died from unnatural deaths are less likely to be reborn into the same family. Without thinking, they simply grab at the first opportunity—any fertile woman having unprotected sex. Stevenson gives some examples of murder victims who are reborn into families they consider totally unsuitable or beneath them in comparison to their former families.

In the case of premature natural deaths, what is involved is less shock and therefore more reflection, and, although I don’t have the statistics, probably longer intervals between death and rebirth, giving these individuals the opportunity to resume life in the family they are most drawn to, which is usually their own.

In the old way of thinking, when a person dies, he or she goes into the afterlife and from there reincarnates again. It is assumed that the person vacates the afterlife to inhabit a new body. It is also assumed that the former personality is subsumed into the new one. Lastly, it is assumed that reincarnation progresses and is sequential. None of this is true. In almost all cases, each of your incarnations is also in the afterlife. What I mean here is not that they are in a place, but that they have turned their focus away from physical reality and onto their new nonlocal dimensions. This change of focus is the only true definition of “dead.” Death is not about the body, it is about consciousness. So a truly dead person is someone who has changed focus, even if the body is still alive.

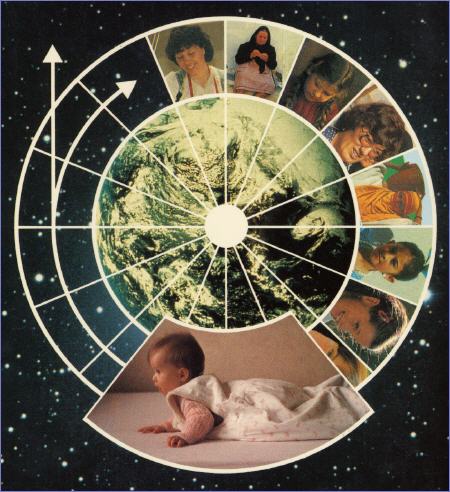

Incarnations are not sequential. They are simultaneous. They radiate out from the master consciousness that gives birth to them — the oversoul or entity — like light from a light bulb, all at once and in all directions. What seems to us to be different time zones are really spacetime camouflages for different psychological spheres. In fact, you may very well have a reincarnation of yourself walking the earth right now. Together, incarnations amass knowledge and experience while alive or dead, which is telepathically shared.

So normally, the core personality changes focus and continues to develop in various nonlocal realities we call the afterlife, while another part of their greater selves, another core personality, reincarnates. That’s the best case scenario and the most common one. However, this is not what happened to at least some of those children who formerly died traumatically. These individuals never changed focus. They were never really “dead.” Instead, without intermission, the same core personality goes on into a new body. Their former lives and their next incarnations are continuous. This is of course the main reason why their memories are so spectacular. One child Stevenson wrote about had murdered someone in his previous life and in the next life was still proud of it. He was also in love with the same prostitute he loved in the life before, and when he was old enough had an affair with her. This is an extraordinary and very rare example of the core personality moving from one body to another without pause. In the intermission phase between lives, they are simply suspended. Supporting this explanation is that only twenty percent of all the children under study, with past deaths both natural and unnatural, had intermission memories.

Bodies can also exhibit this continuity. In several cases Stevenson studied, the wounds from the children’s past-life deaths were clearly imprinted on their reincarnated bodies, usually as birthmarks. For instance, Stevenson interviewed a child who remembered dying from a gunshot wound to the head. The child had two birthmarks, one on the front of his head marking the bullet’s entrance, and another on the back of the head, marking the exit wound. Clearly even the body matrix had stayed much the same.

The cases presented here of reincarnation after the body’s traumatic demise should force us to redefine death as an act concerning consciousness alone, in which the body most often—but not always—plays a role.